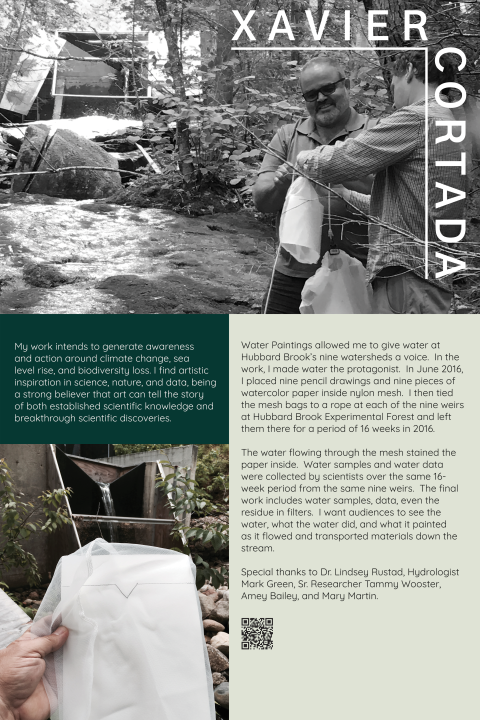

Field Station: Art-Science in the White Mountains Introductory Panel

Long a site of collaboration for scientists, for the last decade the Hubbard Brook Experimental Forest has encouraged artists to join their ongoing conversations. The artists in the exhibition have all spent time in the forest and with the scientists. While the form of their work varies, all of it is in conversation with the ecosystems of the forest and the research community.

Exhibition curated by Meghan C. Doherty; Graphic Design by Inna Horbovtsova, PSU Class of 2023, using photographs by Joe Klementovich.

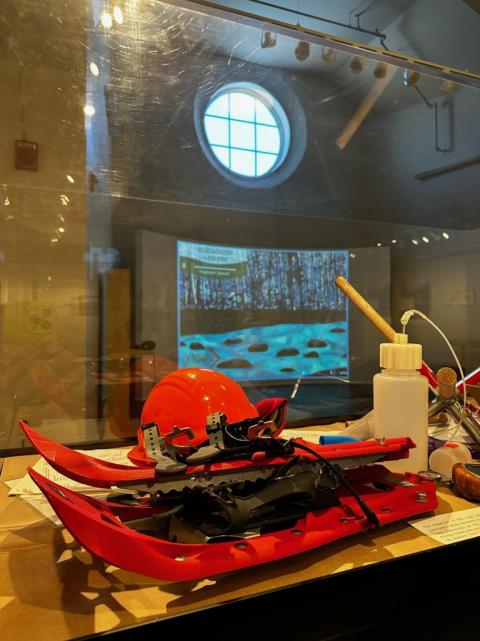

For more about art-science conversations at Long Term Ecological Research sites, watch our panel discussion with Rich Blundell, Peter Groffman, Rita Leduc, Lindsey Rustad, and Leah Wilson.

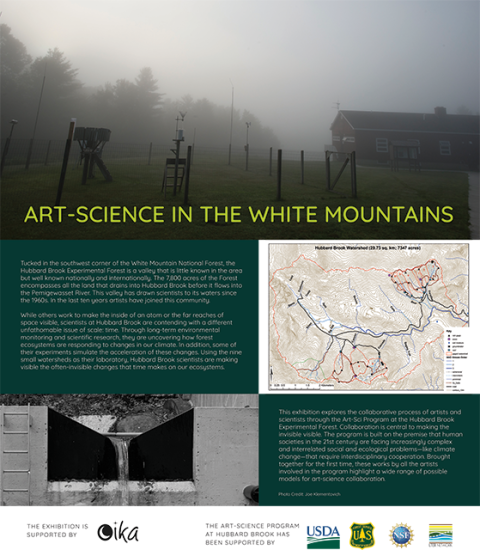

Tucked in the southwest corner of the White Mountain National Forest, the Hubbard Brook Experimental Forest is a valley that is little known in the area but well known nationally and internationally. The 7,800 acres of the Forest encompasses all the land that drains into Hubbard Brook before it flows into the Pemigewasset River. This valley has drawn scientists to its waters since the 1960s. In the last ten years artists have joined this community.

While others work to make the inside of an atom or the far reaches of space visible, scientists at Hubbard Brook are contending with a different unfathomable issue of scale: time. Through long-term environmental monitoring and scientific research, they are uncovering how forest ecosystems are responding to changes in our climate. In addition, some of their experiments simulate the acceleration of these changes. Using the nine small watersheds as their laboratory, Hubbard Brook scientists are making visible the often-invisible changes that time makes on our ecosystems.

This exhibition explores the collaborative process of artists and scientists through the Art-Sci Program at the Hubbard Brook Experimental Forest. Collaboration is central to making the invisible visible. The program is built on the premise that human societies in the 21st century are facing increasingly complex and interrelated social and ecological problems—like climate change—that require interdisciplinary cooperation. Brought together for the first time, these works by all the artists involved in the program highlight a wide range of possible models for art-science collaboration.

Artists

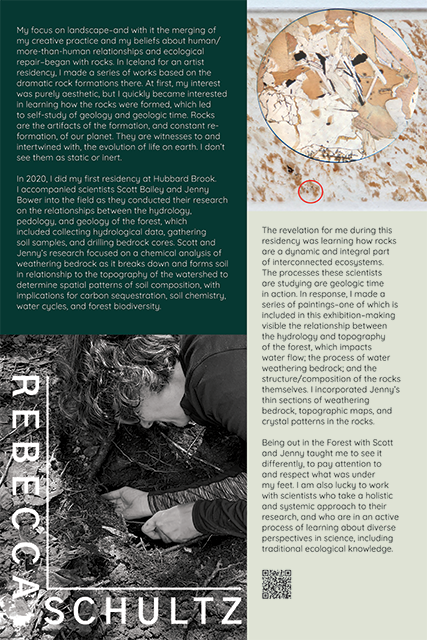

My focus on landscape–and with it the merging of my creative practice and my beliefs about human/more-than-human relationships and ecological repair–began with rocks. In Iceland for an artist residency, I made a series of works based on the dramatic rock formations there. At first, my interest was purely aesthetic, but I quickly became interested in learning how the rocks were formed, which led to self-study of geology and geologic time. Rocks are the artifacts of the formation, and constant re-formation, of our planet. They are witnesses to and intertwined with, the evolution of life on earth. I don’t see them as static or inert.

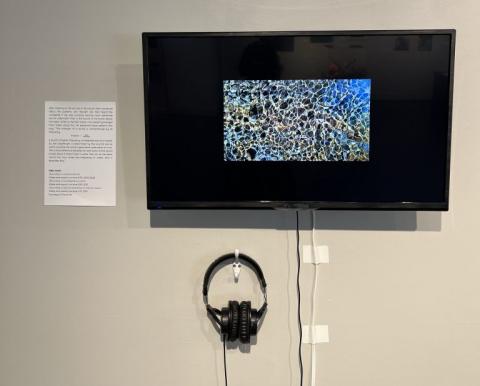

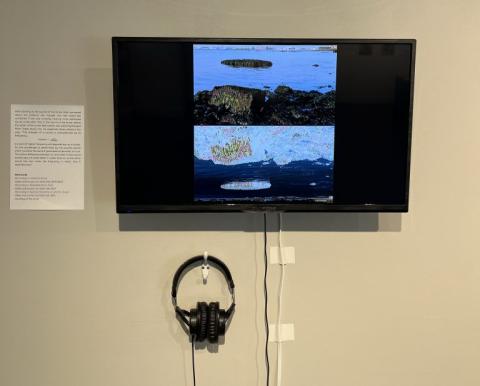

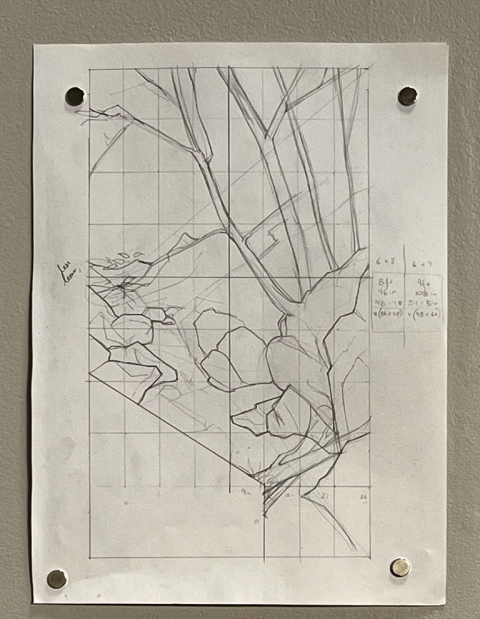

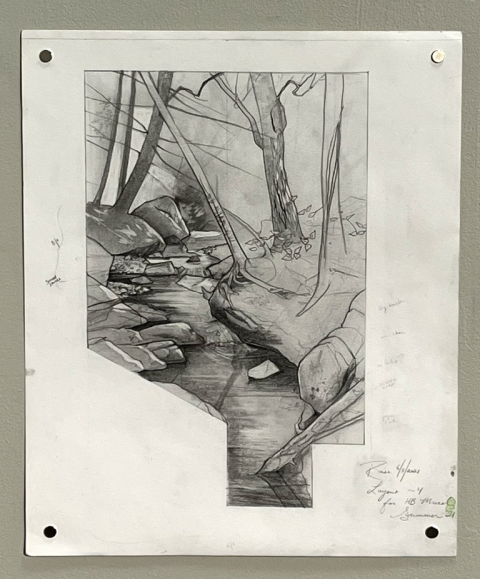

In 2020, I did my first residency at Hubbard Brook. I accompanied scientists Scott Bailey and Jenny Bower into the field as they conducted their research on the relationships between the hydrology, pedology, and geology of the forest, which included collecting hydrological data, gathering soil samples, and drilling bedrock cores. Scott and Jenny’s research focused on a chemical analysis of weathering bedrock as it breaks down and forms soil in relationship to the topography of the watershed to determine spatial patterns of soil composition, with implications for carbon sequestration, soil chemistry, water cycles, and forest biodiversity.

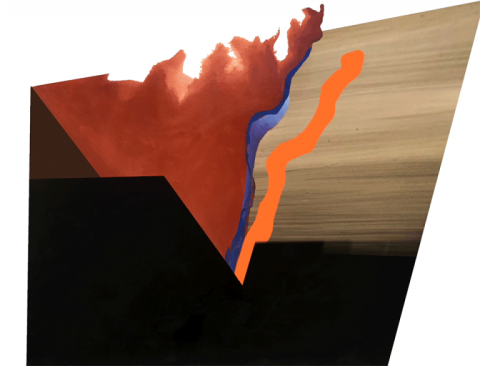

The revelation for me during this residency was learning how rocks are a dynamic and integral part of interconnected ecosystems. The processes these scientists are studying are geologic time in action. In response, I made a series of paintings–one of which is included in this exhibition–making visible the relationship between the hydrology and topography of the forest, which impacts water flow; the process of water weathering bedrock; and the structure/composition of the rocks themselves. I incorporated Jenny’s thin sections of weathering bedrock, topographic maps, and crystal patterns in the rocks.

Being out in the Forest with Scott and Jenny taught me to see it differently, to pay attention to and respect what was under my feet. I am also lucky to work with scientists who take a holistic and systemic approach to their research, and who are in an active process of learning about diverse perspectives in science, including traditional ecological knowledge.

It took me two years to get back to Hubbard Brook, but in the interim I began including foraged and natural materials in my work, and my thinking about the concept of kinship with the more-than-human world evolved. These developments led to an increased focus on soil–both as an art material and as a conduit between bedrock and the living world threading through and growing out of it. During my time at Hubbard Brook in July 2022, I supported Scott Bailey as he conducted validation sampling for a predictive soil map. We spent four days in different parts of the Forest locating sampling points on the map, digging soil pits, doing basic analysis (texture, color, taxonomy), and noting surrounding tree cover. I collected soil samples at each pit. I felt incredibly fortunate to have explored parts of the Forest that even Scott hadn’t seen–including beaver-dammed wetlands and Mount Kineo, its highest point. My studio work that week included pulverizing rock samples for use as pigments, making soil watercolor, and creating chromatographs of seven soil horizons.

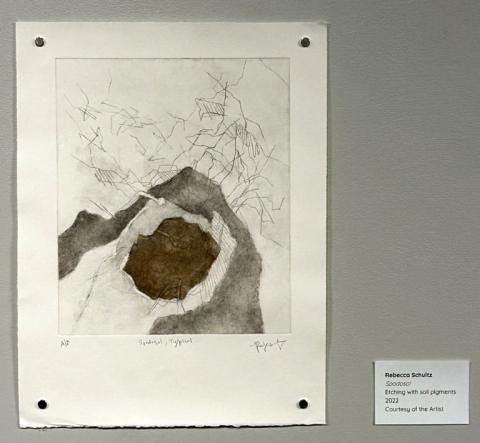

The week at Hubbard Brook allowed me to build upon my practice of making soil pigments. I was particularly fascinated by the differences in color and texture in soil horizons, as well as the form of the pit, with a halo of organic matter surrounding its opening. The etching in this show is based on the image of a typical spodosol, using ink made from soil sampled from three soil horizons. Etching is my favorite printmaking process–it involves materials and equipment that have been in use for more than 500 years. The process of etching a plate—using acid to carve lines in metal—also evokes the process of chemical weathering of bedrock to make soil.

I noticed how differently I felt in the Forest the second time I went; I was no longer anxious about being out there with no other people anywhere around, no trails…instead I felt surrounded by life. It is my aim as an artist to engage as many people as possible in the process of observing, noticing, and rebuilding relationships with the living web that surrounds us. My work at Hubbard Brook has been instrumental in building my practice towards that goal.

Hubbard Brook Chromographs, 2022

Soil horizons, or layers, vary in different parts of a soil profile and across the landscape, determined by mechanisms that stabilize organic matter. But we have a lot to learn about these processes and how land management and climate change may alter soil carbon storage. When Scott saw Rebecca’s chromatographs, which were each made from a different soil horizon, he was struck by how distinct the patterns were. In particular, the pattern shown by the Bh horizon is unique and raises the question about whether there is something particularly different about organic matter quality in this horizon. Comparison of these art pieces is causing scientists to take a closer look at laboratory data to see where there are distinctions, which may lead to new hypotheses about soil formation mechanisms.

Spodosol, Etching with soil pigments, 2022

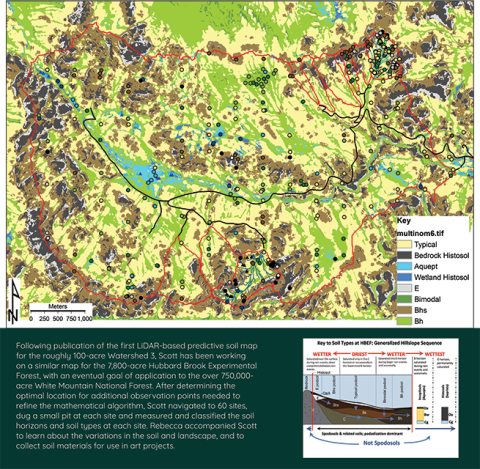

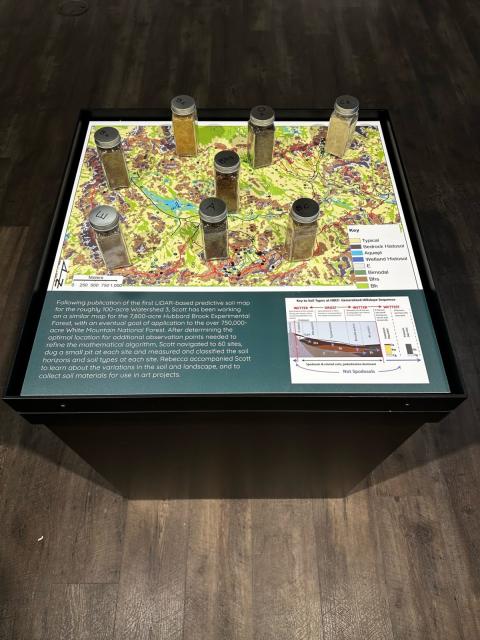

Following publication of the first LiDAR-based predictive soil map for the roughly 100-acre Watershed 3, Scott has been working on a similar map for the 7,800-acre Hubbard Brook Experimental Forest, with an eventual goal of application to the over 750,000-acre White Mountain National Forest. After determining the optimal location for additional observation points needed to refine the mathematical algorithm, Scott navigated to 60 sites, dug a small pit at each site and measured and classified the soil horizons and soil types at each site. Rebecca accompanied Scott to learn about the variations in the soil and landscape, and to collect soil materials for use in art projects.

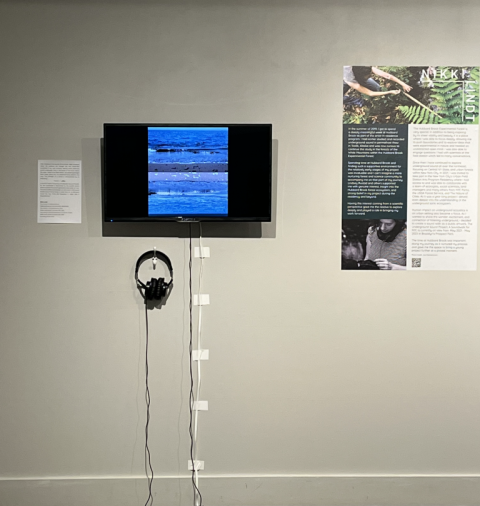

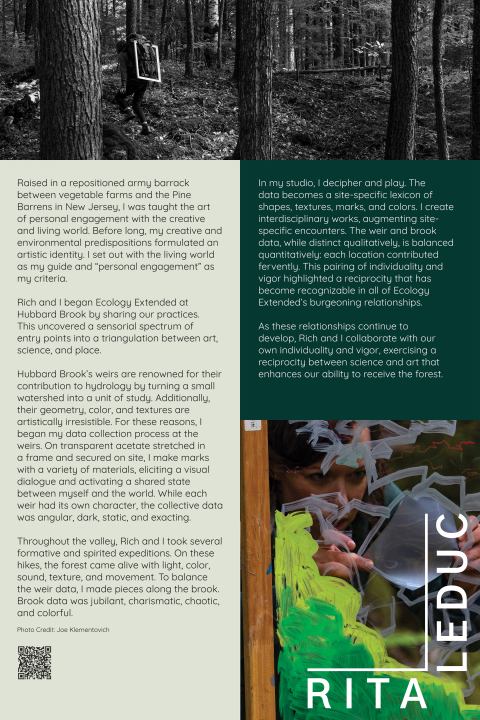

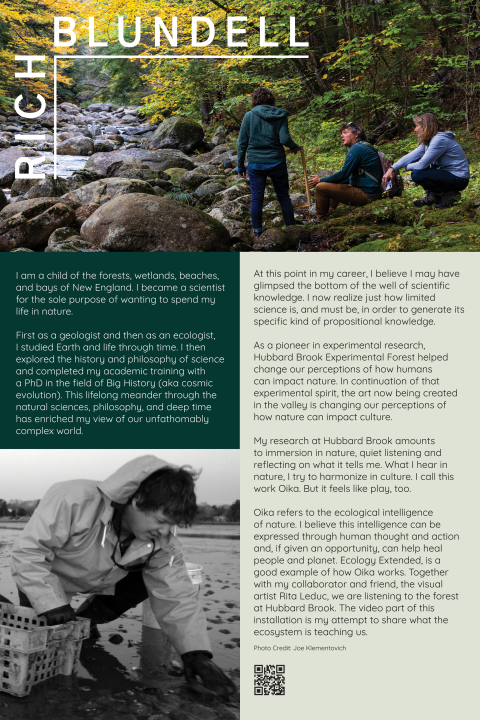

In the summer of 2019, I got to spend a deeply meaningful week at Hubbard Brook as part of the artist-in-residence program. I had earlier studied and recorded underground sound in permafrost thaw in Toolik, Alaska and was now curious to continue this study in the forests of the White Mountains within the Hubbard Brook Experimental Forest.

Spending time at Hubbard Brook and finding such a supportive environment for the relatively early stages of my project was invaluable and I can’t imagine a more nurturing forest and science community to accompany me on that part of my journey. Lindsey Rustad and others supported me with genuine interest, insight into the Hubbard Brook forest ecosystem, and strong belief in my project during the residency and beyond.

Having this interest coming from a scientific perspective gave me the resolve to explore deeply and played a role in bringing my work forward.

The Hubbard Brook Experimental Forest is very special. In addition to being inspiring by its sheer vitality and beauty, it is a place where I was able to focus deeply, allowing me to push boundaries and to explore ideas that were experimental in nature and needed an undistracted open mind. I was also able to engage questions I had with scientists at the field station which led to many conversations.

Since then I have continued to explore underground sound all over the northeast, focusing on Central NY State, and urban forests within New York City. In 2021, I was invited to take part in the New York City’s Urban Field Station Arts Program Residency where I had access to and was able to collaborate with a team of ecologists, social scientists, land managers and many others from NYC Parks, the USDA Forest Service, and The Nature of CIties. As it was a year long project I delved even deeper into the understanding of the underground sonic ecosystem.

Human impact on underground acoustics in an urban setting also became a focus. As I wanted to share the wonder, excitement, and connection of listening underground, I decided to create a sound walk as a public artwork. The Underground Sound Project; A Soundwalk for NYC is currently on view from May 2021 – May 2023 in Brooklyn’s Prospect Park.

The time at Hubbard Brook was important along my journey as it nurtured my process and gave me the space to bring a young project further at a pivotal moment.

After listening to the sounds of the brook, Nikki wondered about the patterns she thought she had heard. She wondered if she was correctly hearing more patterned sound underwater than in the sound of the brook above the water. While at the field station, she asked hydrologist Mark Green about this. He explained those patterns this way: “The strength of a sound is characterized by its frequency.

A sound of higher frequency will degrade less as it travels. So, the wavelength is determined by the sound’s source which would be the same if generated underwater or in air. The critical difference between air and water is that sound travels about 4 times faster in water than air, so the same sound has four times the frequency in water, thus it degrades less.”

To learn more about Nikki Lindt’s work.